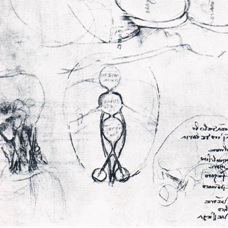

Leonardo da Vinci’s (1452-1519) drawing of the psychophysical question exemplifies a transition from symbolic to iconic signs, which generates new knowledge. In these drawings Leonardo tries to explain how mind and body function together. In 1487, in the Royal Library MSS 12626r and 12627r, he illustrated schematic cross sections of the head and mapped mental capacities, according to the tripartite model. Leonardo probably became familiar with the idea of connecting functional centers to cerebral ventricles through reading the work of Albertus Magnus (1206-1280), who mainly relied on the work of al-Ghazali (1053-1111). As we can see, in 12626r and 12627r, the sensus communis, in which all the senses converge, and the judgment and soul reside, is in the middle ventricle, unlike the tradition in which it’s in the anterior one.

12626r, detail 12627r, detail

We know that Leonardo designated the middle ventricle to the sensus communis since in 12626r, “senso commune” is written on the left side of it, and in 12627r “chomune senso” in it.

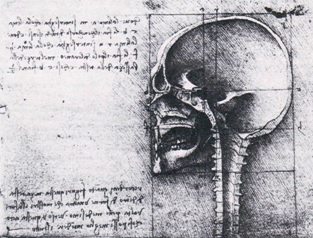

In Royal Library MS 19057r from 1489 we see a different kind of representation, although the attempt to localize mental capacities continues. In the top paragraph of the page Leonardo writes: “Where the line a m, intersects the line c b, will be the confluence of all the senses; and where the line r n, intersects the line h f, will be the pole of the cranium, at a third of the base of the head, and thus c b, will be a half” (Saunders and O’Malley, p. 52).

19057r, detail

Here, unlike in 12626r and 12627r, Leonardo doesn’t specify the mental capacities next to or in the cerebral ventricles. Instead, his method is to direct the viewers’ gaze from the text to the image and vice versa. The skull that he draws from an observation of a real one, defines the space for the discussion. The single letters that he writes in the paragraph and at the ends of the lines (a, m, c, b, r, n, h, f) enable him to point to a specific line. The lines, which he probably drew after and over the image of the skull, help him to direct our look to a specific point by intersections within the image. This point is the “confluence of all the senses”, the sensus communis.

The transition from words as the main signifier of the location of the sensus communis to a very specific point in a drawing that imitates a real skull is a linguistic move from symbols to iconic signs within the same scientific question. This move not only enabled Leonardo to get closer to a point in space, but also to communicate his findings in a way that makes much more sense.

Left image: Leonardo da Vinci, The Musculature of the Leg and the Anatomy of the Head and Neck, 1487. Pen and brown ink on paper, 222 x 290 mm. Windsor, Royal Library, no. 12626r

Right image: Leonardo da Vinci, Miscellaneous Anatomical Drawings, 1487. Pen and brown ink on paper, 203 x 152 mm. Windsor, Royal Library, no. 12627r

Bottom image: Leonardo da Vinci, Two Views of the Skull, 1489. Pen and brown ink on paper, 188 x 134 mm. Windsor, Royal Library, no. 19057r